Growing up in southwest Oklahoma, I knew of Belle Starr (1848-1889) from an early age. Her short, legendary career as an outlaw looms large in the mythic West. From Robbers Cave to the Wichita Mountains, the Sooner State is as full of her legend as any other this side of the Mississippi. Many years later I would discover how much Belle was mythologized specifically by the men of her era, particularly in the sensationalist National Police Gazette published by Richard J. Fox (no relation to our contributor of the same name….that we know of!). In an era before women could vote in the United States, Belle Starr took what she wanted, but with her sudden and still-unsolved murder, the narrative was quickly filled-in by moralists, hearsayers, and fame-chasers.

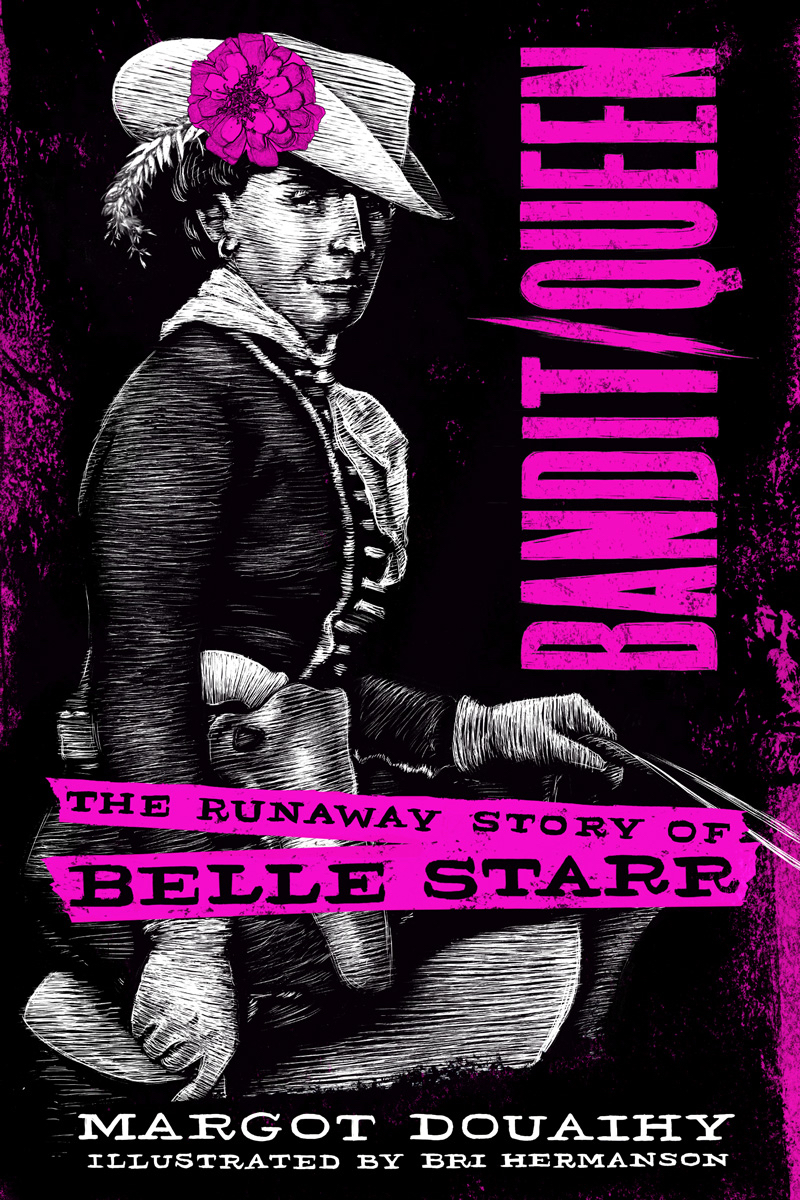

Enter Margot Douaihy and Bri Hermanson. With Bandit Queen: The Runaway Story of Belle Starr, the duo reinstate the outlaw Queen on her outlaw throne. This documentary poetic collection combines persona poems, journalistic remixes, and gorgeous scratchboard artwork to revise and revisit the brief career of one of the most elusive figures of the wild west.

What follows is excerpted from a wonderful 40+ minute virtual convo we three had together. We begin with Bri’s art….

Seth Copeland: They seem very woodcut inspired, would we say?

Bri Hermanson: Absolutely. They’re pen & ink on scratchboard. I draw in pen & ink and I cut into them with knives, so its kind of like the poor man’s woodcut. A lot of these like this [work in the] Police Gazette were done in pen & ink.

Margot Douaihy: You can sort of see how they’re almost sculptural.

BH: The cover illustration is more representative of my typical work. But to do fifteen interior illustrations in a limited amount of time and a limited budget, I had to figure out a way to loosen them up. The first illustration in the book is actually the first one I did. I was like ‘Let’s just do this as an experiment. If it’s terrible [laughs], I’ll do something else.’ And it came out, and I was like ‘Oh this is it, this is right.’

SC: You’re pulling from sources and this is a documentarian type project. There’s so many [pieces] that are headlines. Did you find yourselves thinking in that sort of 19th Century journalistic, almost yellow, mode?

MD: Oh yeah. There’s such a cadenced grace to it all. The insane, hyperbolic language is almost contagious. It is so infectious. There’s this mode of register that it clicks into, so that inspired a lot of both the text and then the subtext in a lot of the poems that I was writing, and I wanted to create a sense of using a language as a perpetrator, too. You have these people that are writing these salacious headlines that are so absurd but also captivating. There’s no fact-checking, so you have all these spurious claims about Belle Starr and her exploits, her husbands and her lovers and her dalliances. I found [speaking in these cadences] really generative; it sent me into a place of persona poetry but also trying to fight back against it and shoot it Belle’s gun [laughs]. I found it, though, quite poetic. Some of the names that they called Belle in these books, like in the Richard K. Fox book: “the vile reptile”–that’s exceptionally beautiful and poetic and lyrical! So you have this lyrical impulse versus the tyrannical, misogynistic, capitalist sense of ‘We’re just gonna say whatever we want, make a buck, and capitalize off this woman,’ but there’s a lot of craft to it. Through this process we read so much and stepping into it was really interesting for me, because I appreciated their craft but I also wanted to fight against it.

SC: You have a figure here who’s been so mythologized, and your Afterword really helps frame that a lot of this is still a big headscratch. And it’s mostly men writing in newsprint at that time and creating these crafted names. Throughout when I was reading this, I thought about “Tombstone Blues” by Bob Dylan. He’s got everybody juxtaposed–he’s got Ma Rainey next to Beethoven–but it’s not Bell Starr, it’s the ghost of Belle Starr. There’s already a whiff of mystery, she’s already a question mark, like it’s a foregone conclusion that she’s unknowable, like so many Western mythic figures.

MD: Foregrounding her haunting rather than her.

SC: Yeah!

MD: There’s so little we can know about Belle Starr in terms of the documents and the archives, because even the archives that we looked at from the Western Historical Society libraries were letters about Belle Starr or hearsay, even the actual Belle Starr Collections. We just tried to think ‘Well, how can we bring any kind of authenticity to an artistic exploration about who this person’ who [gestures to Bri] loomed large in your life.

BH: Oh yeah, big time.

MD: That’s how I learned about Belle Starr, when we went to visit Bri’s family for the first time and we went into the Pioneer Women’s Museum in Ponca City, and there was this exhibit of her with the “three female outlaws” exhibit, which was so…just…

BH: Only in Oklahoma!

SC: Oh, very. So Okie.

MD: So exquisite and complicated.

BH: My Grandma used to read those dimestore Western books about her all the time.

MD: There are just so many labyrinthine tales. We were astonished by it the more we dug into it, which is fun and confusing in a way, too, because the more you research the less you know.

SC: We talked about the myth built up by the male gaze, but I think you guys center a person. She’s also got a romantic life, she’s a mother, she plays the piano, and all that’s in the book…but also she’s a badass woman! What was it like getting into the voice?

MD: Musicality. We really wanted to center the musicality because one of the things that was very clear was that she was an excellent pianist, and that was undisputed. I wanted to center musicality and sometimes some calculated, surreal types of lexical movements that had rhythm but had a kind of wink/nod intelligence of a person who is confident enough to use slang. We incorporate some of that dialogue or internal dialoge of reported speech w/ the archivable materials, and that back-talk or call-and-response, but locating the voice really started with the musicality and just weird rhythm and thinking about galloping and someone just running, running from domesticity, running toward her lovers…a voice that’s really strong but [with] some authenticity to the time. Poetry’s the perfect playground to experiment with voice, but I find that we do need an internal logic to make it land.

We spend some time admiring “Wild,” an early piece of the book, the bold and attention-demanding arrangement of the text blocks.

MD: That’s what’s amazing about documentary poetry, that to bring the artist’s voice into real people, real happening, real events, does strangely insist upon a kind of idiosyncratic exploration or experimentation.

BH: I had a lot of personal, like, “Oh my God I cant screw this up, this is too important to my people! I can’t make a bad drawing of Belle Starr!” Be tarred and feathered.

MD: I mean, her mom has a branding iron over the bed!

SC: Yeah, you gotta do Belle justice or you’re in big trouble. Was it a collaborative thing with the [illustrations’] titles?

BH: That was collaborative, yeah. A lot of [the National Police Gazette]’s full-pagers have captions at the bottom [shows an example]. We got pretty poetic with some of the titles; they’re not super straightforward and I think that’s kind of a fun Easter egg in the book.

SC: With docupoetics, it’s a pain in the ass sometimes not to get too expository.

MD: Totally. You have to have trust in the reader and hopefully build enough interest and thicken it and make it sticky enough that if people want to learn more, that’s the best case scenario. Over-exposition is just deadly, it’s so decelerating and its sometimes simply just condescending.

SC: I think you hit the nail on the head by describing it as decelerating if its bad, because what that makes you do as the rhetor is that you have to be very discerning with your choices. ‘What’s important and how can I say in the most…not succinct way but in the most useful way. After Bri introduced you to the story of Belle Starr, Margot, what in particular resonated with you? We’ve got the Okie here [gestures at Bri], so what gripped you the most about her story?

MD: A woman who asked the question ‘What is my authentic life?’ and pursued it to an untimely, quick end at the young age of forty-one, almost forty-two. I’m close to that age. I find it fascinating that we have a record of a woman who was born into a relatively comfortable life, not that anything really was during the Civil War–

BH: Especially for a woman.

MD: Yeah, especially for a woman, but had this kind of domestic plan and Y/X axis to follow, and left it, repudiated it, and literally went on the run and created a life for herself and became a mother, became a wife, but [also] became a gangleader and became a woman in her own terms. And her fashion! Her flair and contradictions are so interesting.

SC: Tell me about the choices made with the illustrations and working together. Obviously, some of them are responses to specific poems, but a few of them I imagine came independently as well?

BH: That’s true. There was a lot of back-and-forth. There were some that that Margot asked for and wanted as visuals. There were some that I was resistant to that we ended up doing, and I’m glad that they’re in the book.

One image Bri was initially resistant to doing depicts “Belle Starr & Her Lovers, Husbands, Kin, Neighbor,” which she’s now glad is in the book. Margot cites this as possibly her favorite image in the collection. “They’re all so dapper in their own ways,” Margot says of the men depicted. “I love that.” Then we return to Belle…

MD: The way Bri drew her, she’s shrouded by her hat so she’s almost obscured by herself. There’s so much to read into, but my eye is just so pulled into her face. You have this character that both wants to be seen but wants to be concealed.

BH: Throughout the book, I never wanted you to be able to fully see her. She’s always somehow obscured or small. Because in a way she is unknowable, and even as we try to know her, she still needs to be slippery.

SC: I think there are some poignant queer analogues in this story. Can you speak on that?

MD: Yeah. Definitely. I just thought it was interesting to think about the question of who we are as artists and interpreters, and so I just wanted to break the fourth wall in [the poem] “Voila!” because there’s just no sense in pretending that I’m her. The queerness was essential for me because so many voices are erased from history. Even me growing up in the 80s-90s, it was a “don’t ask/don’t tell era,” so I feel almost an obligation, like its incumbent on me to imagine what queernes might have been at that time. So that’s where the poem “Dizzy” comes from, thinking of women that might’ve been besotted with Belle perhaps because she was somewhat free and famous but also maybe because she was beautiful and had a crush on her in the same way that men did. So that felt like a necessary exploration.

Bandit Queen will be released by Clemson University Press this month.

NEXT >

< BACK

INDEX